Leading cancer doctor, Martin Gore, dies after routine yellow fever vaccine

A leading British cancer expert, Martin Gore, has died suddenly after receiving a routine yellow fever vaccination.

Gore, who was described as a “pioneer” in his field by Prince William, died Thursday morning after receiving the vaccine, which is recommended to travelers visiting sub-Saharan Africa, most of South America, and parts of Central American and the Caribbean.

Like most vaccines, officials report typical side effects of the vaccine include headaches, muscle pain, mild fever and soreness at the injection site. But Gore’s death casts light on the rarer, more severe side effects that the CDC and NHS fail to stress.

One such side effect is viscerotropic disease—a rare but dangerous side effect of yellow fever vaccinations where an illness similar to wild-type yellow fever proliferates in multiple organs.

Yellow fever vaccine riskier for the elderly

The WHO has reported that there is a higher risk of viscerotropic disease have occurred in primary vaccines in the elderly: “Two out of the five studies found a significantly higher rate of YEL-AVD among the elderly population.”

All vaccines have risks associated with them, not just the superficial redness and soreness at the injection site. And some people carry higher risks than others.

Instead of focusing on finding potential risk factors in vaccine recipients, officials are repeating the same talking points.

“The yellow fever vaccine is extremely effective in protection against this infection and has been used worldwide for many years,” Martin Goodier, assistant professor in immunology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine said. “Because of the widespread use of the vaccine we can say with certainty that such adverse events are rare. The benefits to health of vaccination far outweigh any potential risk.”

Jonathan Ball, professor of molecular virology at the University of Nottingham, said that the yellow fever vaccine is “very safe.” Notably, he pointed to reports which suggest that the risk of developing “vaccine-associated viscerotropic disease” increase to around 12 cases per million vaccine doses used, up from three cases per million in the under-60 age group. However, he stated that it still “makes sense” for individuals in “at risk” age groups to get vaccinated if the risk of exposure to the virus is very high.

Does the vaccine make sense?

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains particularly in the back, and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In about 15% of people, within a day of improving the fever comes back, abdominal pain occurs, and liver damage begins causing yellow skin. If this occurs, the risk of bleeding and kidney problems is also increased.

Given that and the risk of serious side effects, the vaccine may not make sense for everyone.

We echo the recommendations that have come out research from the Mayo Clinic:

- Abandon a one-size- (and dose-) fits-all vaccine approach for all vaccines and all persons.

- Predict the likelihood of a significant adverse event to a vaccine.

- Decide the number of doses likely to be needed to induce a sufficient response to a vaccine.

- Design and develop new vaccines and studies to prove their efficacy and safety in such a way as to begin to use them in an individualized manner.

- Identify approaches to vaccination for individuals and groups (based on age, gender, race, other) based on genetic predilections to vaccine response and reactivity.

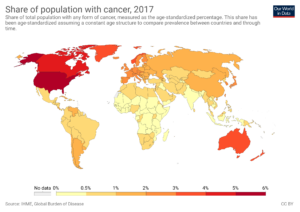

About Martin Gore

Gore was an oncologist for more than 35 years, and first joined the Royal Marsden in 1978 as a senior house officer. He was appointed medical director of the trust in 2006, and held the role for 10 years until he stepped down in January 2016.

London’s Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, where Gore worked for more than 30 years, expressed its “deep sadness” following the announcement of his death.

“Martin was at the heart of The Royal Marsden’s life and work in research, treatment and the training of our new oncologists,” the hospital said in a statement. “His contribution as medical director for 10 years, a trustee of The Royal Marsden Cancer Charity, and as a clinician is unparalleled.”