The Circadian Diet

When you eat may be as important as what you eat, studies are showing. Eating certain foods at certain times of day is important to a healthy diet. This appropriation of the diet that we’ve been describing for a dozen years is the crux of the circadian diet method now being promoted in books and popular trends in intermittent fasting.

“It’s well known that by changing or disrupting our normal daily cycles, you increase your risk of many pathologies,” said Dr. Sassone-Corsi, who recently published a paper on the interplay between nutrition, metabolism and circadian rhythms:

The circadian clock, a highly specialized, hierarchical network of biological pacemakers, directs and maintains proper rhythms in endocrine and metabolic pathways required for organism homeostasis. The clock adapts to environmental changes, specifically daily light-dark cycles, as well as rhythmic food intake. Nutritional challenges reprogram the clock, while time-specific food intake has been shown to have profound consequences on physiology. Importantly, a critical role in the clock-nutrition interplay appears to be played by the microbiota. The circadian clock appears to operate as a critical interface between nutrition and homeostasis, calling for more attention on the beneficial effects of chrono-nutrition.

In one experiment, scientists found that assigning healthy adults to delay their bedtimes and wake up later than normal for 10 days — throwing their circadian rhythms and their eating patterns out of sync — raised their blood pressure and impaired their insulin and blood sugar control. Another study found that forcing people to stay up late just a few nights in a row resulted in quick weight gain and reduced insulin sensitivity, changes linked to diabetes.

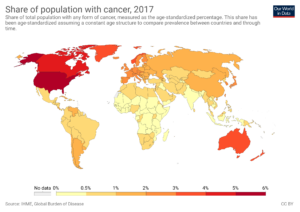

Nighttime shift work is linked to obesity, diabetes, some cancers and heart disease. While socioeconomic factors are likely to play a role, studies suggest that circadian disruption can directly lead to poor health.

In 2012, Dr. Panda and his colleagues at the Salk Institute took genetically identical mice and split them into two groups. One had round-the-clock access to high-fat, high-sugar foods. The other ate the same foods but in an eight-hour daily window. Despite both groups consuming the same amount of calories, the mice that ate whenever they wanted got fat and sick while the mice on the time-restricted regimen did not: They were protected from obesity, fatty liver and metabolic disease.

Our research has shown that eating specific foods during that circadian diet window is even more beneficial.

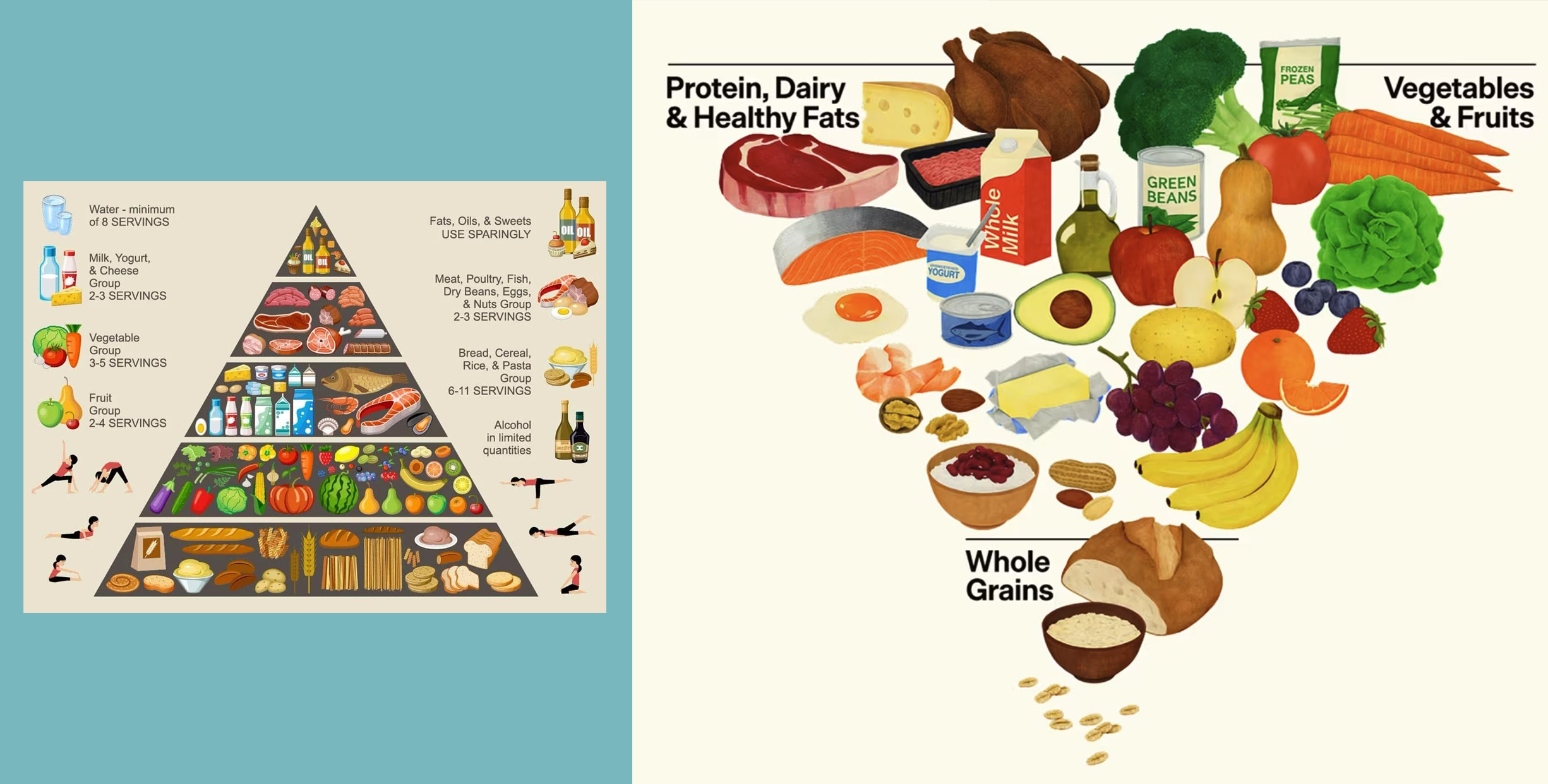

Throughout the day, while consuming a consistent amount of LoS Hi-Fi foods, the Paleo Family dieter’s metabolism is running evenly. We recommend physical exercise in the late afternoon or early evening (after work is perfect), during which the body is physically stressed. Hunger should subside throughout the physical exercise, but when it returns, we recommend a large meal full of healthy high-protein foods like fish, pork, or chicken. With this plan, one can eat to his heart’s content around dinnertime, as long as one is eating high-protein, high-fat foods. Low- or zero-sugar veggies (zucchini, broccoli) are fine for dinner but reduce the effectiveness of the plan. And as a guy with the most wicked sweet tooth known to humanity, it kills me to say it, but anything with sugar should be avoided after dinner as well. That’s right, no pie for dessert.

Putting it in terms of modern fad diets, you should eat Whole 30 (but with some grains) throughout the day and the Keto diet after exercise. All of this is documented in Zero to Paleo: appropriation of one’s diet optimizes digestion and overall health by creating a natural change the digestive process that coincides perfectly with your normal sleep cycles.