New Drugs Won’t Slow the Suicide Epidemic; They Might Be the Cause

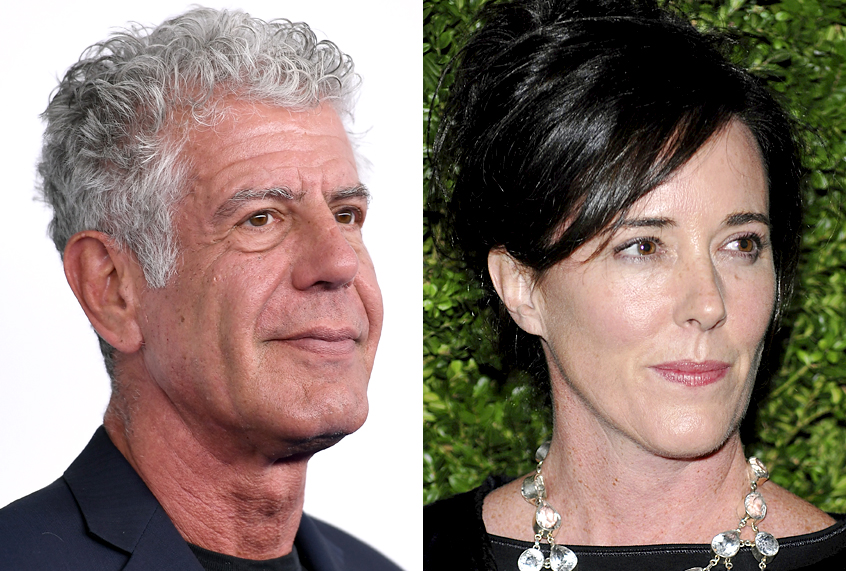

Designer Kate Spade attends the CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund finalists event at Skylight Studios on Monday, Nov. 17, 2008 in New York. (AP Photo/Evan Agostini)

The recent celebrity suicides of Kate Spade and Anthony Bourdain have alerted media to an epidemic of suicide in the United States over the last 15 years: U.S. health authorities said on Thursday that there had been a sharp rise in suicide rates across the country since the beginning of the century and called for a comprehensive approach to addressing depression.

Some say this highlights a need for “new anti-depression drugs” of which there are obstacles today:

With the availability of numerous cheap generic antidepressants, many of which offer only marginal benefit, developing medicines for depression is a tough sell.

But as we describe in the forthcoming Paleo Family, psychiatric drugs have an infamous history of fixing symptoms to problems that aren’t really there and what’s worse, causing dependence and exacerbating symptoms:

In 1952, French surgeon and psychologist Henri Laborit saw something unexpected in a new antihistamine called Chlorpromazine (CZP). In early trials, he found that the drug caused disinterest without loss of consciousness and with only a slight tendency to sleep. He persuaded doctors at the military hospital in Paris to try the drug on one of their patients with psychosis.

They administered 50 mg of CZP to a 24-year-old severely agitated psychotic (manic) male named Jacques Lh. The patient was instantly calmed but the drug only lasted a few hours, so multiple doses were required. The multiple intravenous shots irritated Jacques so the physicians were forced to incorporate other sedative methods such as barbiturates and electroshock therapy. But after 20 days of therapy including 855 mg of CZP, Jacques was ready “to resume normal life.” It was an unprecedented recovery.

The drug was used in clinical investigations throughout Europe that year and spread around the globe by 1955. Chlorpromazine was consistently found to be effective in calming psychotic patients without substantial adverse side effects. By the time the name brand Thorazine was released in the United States, CZP had launched a psychopharmacological revolution and changed the course of history.

Leonard Cook of the American drug company Smith, Kline & French was able to devise a test to distinguish the effects of CZP from barbiturates and earlier sedatives. He determined that CZP blocks the avoidance response activity in the brain common during psychotic episodes while leaving the motor reflex unaffected. With this standard established, pharmaceutical manufacturers began developing several similar drugs.

In 1957, an American chemist working for Hoffmann-La Roche, Leo Sternbach, was ready to trash the last of a series of compounds he was investigating, all of which had been ineffective. He decided to complete the series anyway and was surprised to discover muscle-relaxing and sedative properties in the drug. Instead of the last in a series of failures, that compound turned out to be the first in a series of stunning pharmacological successes: benzodiazepenes. He would go on to develop Librium and Valium, which went on to dominate the market.

By 1960, the psychiatric drug target market had expanded from people with serious psychotic disorders to people with commonplace complaints. They took mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, antidepressants, and anti-anxiety drugs–most of which were discovered accidentally–for stress, aggression, and just “feeling a bit off.” The sedative lithium and the first antidepressant Tofranil share a similar accidental history: researchers were investigating chemicals for one condition that ended up being beneficial for the symptoms of another. Accidental medical discoveries are not unique to psychiatric drugs as we’ve seen in previous chapters, but what seems to be unique for this group is that researchers didn’t know the effective mechanism of the drugs even after they were discovered. For each of these drugs, researchers never had a comprehensive biochemical framework to test—they just got lucky treating symptoms.

Trying to make up for this obvious scientific gap—at least for antidepressants—Joseph Schildkraut, a psychiatrist at the National Institute of Mental Health, took on the task of figuring out how they worked. In 1965, he published a paper in the American Journal of Psychiatry asserting the chemical imbalance theory of affective disorders. He posited that people with depression had a chemical imbalance, specifically with the neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine.

Nearly a decade after antidepressants were released to the market, manufacturers and doctors finally had a precise medical framework for how they worked. Antidepressant popularity took off, both with prescribers and manufacturers. Psychiatry had figured out depression and how to treat it. The only problem was that the theory was completely wrong.

As brain science became more sophisticated, researchers found that antidepressants worked on serotonin, not dopamine and norepinephrine. And even when that was established, study after study failed to show a serotonin imbalance in people with chronic depression. Antidepressants had worked on an unsuspected neurotransmitter that evidently didn’t have anything to do with depression. As one study put it, “The literature reviewed here strongly suggests that the depletion of brain norepinephrine, dopamine or serotonin is in itself not sufficient to account for the development of the clinical syndrome of depression.” Even Schildkraut had admitted his chemical imbalance theory was, “At best a reductionistic oversimplification of a very complex biological state.”

As brain science became more sophisticated, researchers found that antidepressants worked on serotonin, not dopamine and norepinephrine. And even when that was established, study after study failed to show a serotonin imbalance in people with chronic depression. Antidepressants had worked on an unsuspected neurotransmitter that evidently didn’t have anything to do with depression. As one study put it, “The literature reviewed here strongly suggests that the depletion of brain norepinephrine, dopamine or serotonin is in itself not sufficient to account for the development of the clinical syndrome of depression.” Even Schildkraut had admitted his chemical imbalance theory was, “At best a reductionistic oversimplification of a very complex biological state.”

So, did manufacturers and doctors scale back on antidepressants when these studies were published? Not remotely. They doubled down on the imbalance theory and produced the next generation of drugs to combat the mythological disease: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), including Prozac, Zoloft, and Paxil. But after decades of SSRI use, the data on the efficacy of these drugs are inconclusive at best and damning at worst. A comprehensive analysis of antidepressants in 2002 found that users’ conditions improved on the drugs but that the improvement from the highest dose was no different than improvement from the lowest dose. Also, SSRI drugs were shown to be no more effective than placebo.

Shortly thereafter, Giovanni Fava posed the question, Can Long-term Treatment with Antidepressant Drugs Worsen the Course of Depression? He answered that in the affirmative. Antidepressants increased manic behavior in depressed patients and made them dependent on the drugs causing severe withdrawal symptoms. They also made healthy people depressed and some suicidal. He wrote, “The correlation between duration of antidepressant drug treatment and likelihood of relapse on discontinuation may suggest that it is not simply a matter of failure to protect, but that a neurobiological mechanism increasing vulnerability may be involved.” In other words, antidepressants supposedly designed to correct a chemical imbalance actually end up causing one.

As Robert Whitaker laid out in the thorough exploration of psychiatric medication, Anatomy of an Epidemic:

We have been focusing on the role that psychiatry and its medications may be playing in this epidemic, and the evidence is quite clear. First, by greatly expanding diagnostic boundaries, psychiatry is inviting an ever-greater number of children and adults into the mental illness camp. Second, those so diagnosed are then treated with psychiatric medications that increase the likelihood they will become chronically ill. Many treated with psychotropics end up with new and more severe psychiatric symptoms, physically unwell, and cognitively impaired. This is the tragic story writ large in five decades of scientific literature.

And we’re seeing the impact as the epidemic worsens. A recent report from Blue Cross and Blue Shield showed that depression alone accounts for 9 million patients in the United States and the numbers are rising. From 2013 to 2018, diagnoses of major depression have risen 33 percent and that rise has been most dramatic in young people (depression is up 47 percent in millennials and an astounding 65 percent of adolescent girls). We’re not claiming that these people aren’t ill and that they don’t need treatment, but that the go-to treatment by establishment medicine isn’t helping; it’s most likely contributing to the problem. Any dispassionate observer of the effect of psychiatric medication will conclude that it is like adding fuel to the mental disorder fire.

New psychiatric medications wouldn’t have saved Kate Spade or Anthony Bourdain. It’s looking more and more likely that they cause the problem in the first place.

Resources

Chlorpromazine: Ban, Thomas A. “Fifty Years Chlorpromazine: A Historical Perspective.” Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 3.4 (2007): 495–500. Print.

Librium and Valium: Greenberg, Gary. “The Psychiatric Drug Crisis.” The New Yorker, The New Yorker, 19 June 2017, www.newyorker.com/tech/elements/the-psychiatric-drug-crisis.

No correlation between neurotransmitters and depression: Mendels J., 1974, Brain biogenic amine depletion and mood, Archives of General Psychiatry, 30: 447- 51

Fava paper: Fava, Giovanni A. “Can Long-Term Treatment With Antidepressant Drugs Worsen the Course of Depression?” The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, vol. 64, no. 2, 2003, pp. 123–133., doi:10.4088/jcp.v64n0204.

Whitaker quote: Whitaker, Robert. Anatomy of an Epidemic: Magic Bullets, Psychiatric Drugs, and the Astonishing Rise of Mental Illness in America. Broadway Books, 2015 p. 209.

Blue Cross Blue Shield Report: “Major Depression: The Impact on Overall Health.” Blue Cross Blue Shield, www.bcbs.com/the-health-of-america/reports/major-depression-the-impact-overall-health.