Antibiotic Overuse Tied to Rise in Autism Through Microbiome Disruption

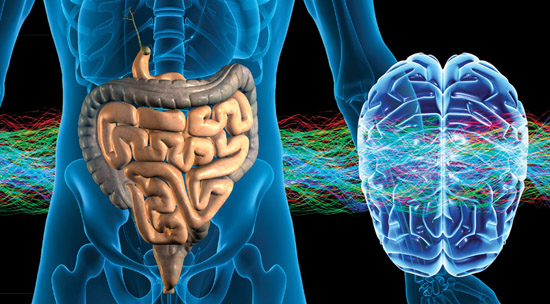

The gut/brain connection is getting more attention as study after study is finding a connection between gastrointestinal flora and neuro-cognitive development and diseases such as autism spectrum disorder. We’re finding that there may be an antibiotics-autism link.

A recent literature review in Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience lays out the connection with mounting evidence.

First, there is a clear correlation between people with autism and gastrointestinal disorders:

GI symptoms occur in about half of children with ASD, and the prevalence increases as children get older (Chaidez et al., 2014). Moreover, the severity of autism symptoms is related to the occurrence of problems in the gastrointestinal tract (Wang et al., 2011). Reported problems included chronic constipation, chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), gas and bloating. A multicenter study of over 14,000 individuals with ASD revealed a higher prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and other GI disorders in patients with ASD as compared to controls (Kohane et al., 2012). The digestive tract of children with autism revealed substantial differences compared to neuro-typical children including abnormal intestinal permeability, inflammation and different composition of intestinal microbes.

Considering this, it’s likely that there is a similar cause for GI disorders and autism. So, what could the cause be? One hypothesis is that antibiotic treatment can lead to a disruption of healthy gut flora:

Antibiotics significantly shift the structure of the microbial community (Dethlefsen et al., 2008; Simon et al., 2015), changing the metabolic status of the gut (Ponziani et al., 2016). Some of the changes caused by antibiotics are transient and can be reversed at the end of the treatment, while others seem irreversible. Most importantly, it has been observed that gut bacteria present a lower capacity to produce proteins, as well as display deficiencies in key activities, during and after the antibiotic treatment. For instance, antibiotics decrease the ability to absorb iron, to digest certain foods and to produce essential molecules (Pérez-Cobas et al., 2013). Previously it was assumed that short-term antibiotic treatment would alter gut microbe composition only for a short time, however, this is not the case (Jernberg et al., 2010). Even a relatively short course of antibiotics can lead to alteration in gut microbiota, which in turn can lead to severe consequences such as inflammation, immune dysregulation, allergies, infections, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, metabolic issues, GI disease such as Crohn’s, IBD, yeast overgrowth, chronic constipation and diarrhea (Jernberg et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2009; Ubeda et al., 2010; Sobhani et al., 2011; Buffie et al., 2012; Rutten et al., 2015; Lau et al., 2017; Ni et al., 2017).

We’ve documented the serious problems associated with superfluous antibiotic use in the West, but now it’s clear that we were just scratching the surface. The gut microbiome is so important to neurological development and the scorched-Earth policy of antibiotics does such damage to that microbiome, that the issue is likely much bigger than we previously thought.

Autism spectrum disorder, which began to skyrocket in incidence 30 years ago is now seen in 1 in 59 children. It is becoming clear that antibiotics have played a major role in that:

In 2010 there were nearly 23 million courses of Amoxicillin or Augmentin prescribed to children in the United States and more than 6.5 million of those courses were for children under the age of two (Chai et al., 2012; Blaser, 2014). Studies have shown that children with autism have had significantly more ear infections than control groups, leading to more antibiotic prescriptions (Niehus and Lord, 2006; Adams et al., 2016; Leung and Wong, 2017). Furthermore, another study showed that 34.5% of children with autism had used extensive and repeated broad-spectrum antibiotic treatments (>6 courses) compared to control group (0% with more than 6 courses) (Parracho et al., 2005). In fact, a higher proportion of 54.5% of the children with autism had received more than six courses of antibiotics suggesting frequent over-prescription of antibiotics. Further prospective studies are warranted to understand how the overuse of antibiotics in the 1st years of life might disrupt the gut–brain axis and lead to the development of future neurological disorders including autism.

There has been a lot of talk about a vaccine-autism link and, while that connection remains unclear, it’s possible that, as at least six vaccines list ear infections as side effects, that could lead to the adverse side effect followed by treatment with antibiotics.

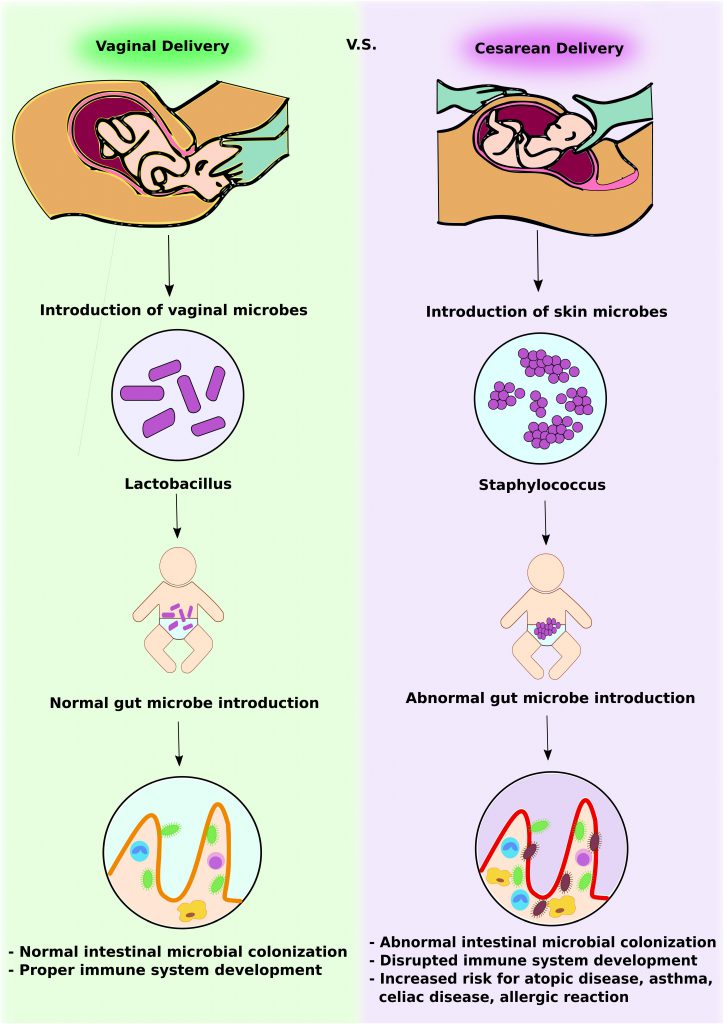

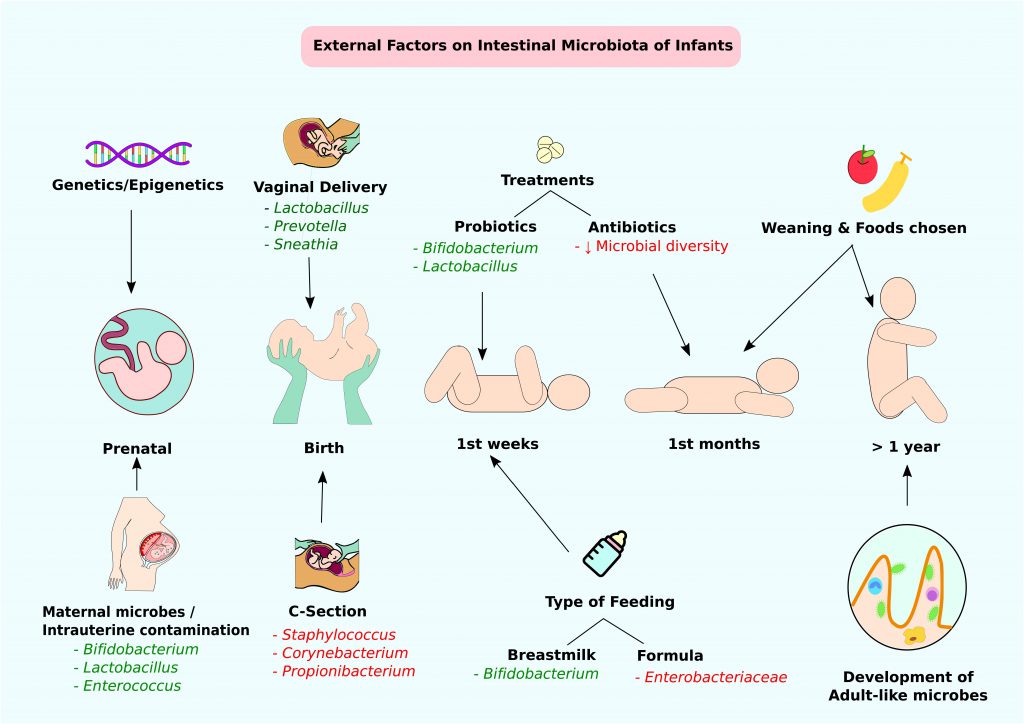

There are other factors that affect the gastrointestinal microbiome, which is why the gut/brain connection has been so elusive to researchers. But there are two other factors that have a clear effect: vaginal birth, which introduces healthy gut flora into the newborn naturally whereas C-section delivery may introduce pathogenic flora into the newborn, and breastfeeding, which continues to support the GI microbiome with probiotics.